As I said in my post yesterday, on past visits I've seen major exhibitions at the John Michael Kohler Art Center for most of the artists whose work is included at the new Art Preserve. The one major artist whose work I had not seen was Nek Chand.

The new building devotes a large amount of the third floor to his work. Chand was an Indian (and Hindu) road inspector in the Punjab region for most of his adult life. There's a city there called Chandigarh, which the newly independent Indian government commissioned by the modernist architect Le Corbusier around 1950. In the process, its construction destroyed multiple Indian villages. Chandigarh is where Chand lived and worked.His story practically gives me goosebumps. According to the JKMAC's Healing Properties exhibit book from their show about him and his work in 2000,

In 1958, while working...for the public works department, Nek Chand began, illegally, to collect, sort, and store uniquely shaped stones and rubble from the ruined villages in a hidden location outside Chandigarh [in] a zone of densely vegetated scrubland... a monsoonal gorge... infested with malaria-bearing mosquitoes, loved by cobras. To this inhospitable place, Nek Chand transported his findings from the city dumps by bicycle during the night, holding a burning tire to light his way.

In 1965, he was ready. He began to transform his considerable holdings into a massive garden of concrete figures and forms inlaid with his rescued shards and stones. Daily he labored, after his regular workday was done and on his days off. The land he worked on was government property, strictly sanctioned against any kind of building or private use. For years he worked in secrecy...

In 1972, a crew of anti-malaria workers came upon the site, which by then Chand had filled with almost 2,000 figures. But instead of destroying the site and Chand's work, the Indian government quickly gave in to public support and not only didn't destroy it, they promoted Chand from his job to become superintendent of the Rock Garden and gave him a staff and equipment.

With this, he organized one of the largest recycling programs in Asia and kept adding on to the garden for decades: terraces, waterfalls, arcades, and more statues.

As Chand's reputation grew, he created art installations in other major cities of the world, including the works in the Kohler collection; the works at the Art Preserve were not removed from the Chandigarh garden.

These women reaching were the first figures I saw in the Art Preserve gallery. Their flowing fabrics and the use of broken ceramics are what caught me. (Note: I didn't know much if any of the story of how Nek Chand came to make these sculptures when I was viewing these pieces.)

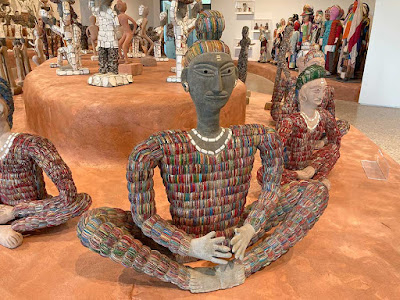

The seated figures are Saddhus, ascetic men who have devoted their lives to contemplation and self-denial.

I love the blue turban on this figure.

And the green turban on this one. Their faces are also exquisite.

By now you may be wondering what that material is on the turbans, or on this red bird. It's broken bangle bracelets.

Most of the work in the Kohler collection is made from concrete, but there's one set of cloth

figures like these (1990–99) that were used for festivals, parades, and

other celebrations at the garden. They're made from rags and discarded

clothes.

This is another part of the Healing Properties exhibit book that I especially like, which contrasts Le Corbusier's nearby city of antiseptic planes and right angles (and cheap construction) with the garden:

Nek Chand's Rock Garden is loved for all that the city of Chandigarh is not. His environment is deeply rooted in the regional folk styles of art and architecture and literally grew from the villages that were there before it. Following an Indian aesthetic, it is crowded and colorful and has emerged from the landscape a day at a time.

According to an Indian art scholar cited in the book, the garden is also part of a classical Indian tradition of art installations, made in response to a particular environment, which existed before Western ideas of art installations.

Finally, the exhibit book told me that it was important to Chand that his sculptures be seen in numbers, that they are not about individual pieces but about their interplay. And that's how the Art Preserve has set up this permanent exhibit:

These figures carrying baskets on their heads are a reminder both of how common that practice is and of the menial role that Indian people played in British colonialism.

This figure carrying a basket behind his back (maybe as a surprise?) has extra-decorative ceramic clothing. I don't know what the story is, but it captured my attention.

I doubt I will ever see the Rock Garden near Chandigarh in person. If you look around for photos of it online, you'll find lots, though usually not many on any single site. This page has a number of good ones. The sculptures at Kohler don't really prepare you for what it's like. 40 acres! And much more architectural.

What a vision and an artist.

__

Other posts about the Kohler Art Preserve:

Kohler Art Preserve: Restrooms

Almost All the Artists But One at the Art Preserve

__

Photo of Nek Chand (2007) by Gilles Probst from the Wikimedia Commons.

No comments:

Post a Comment