The Walker Art Center's current show, Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia has its ups and downs. It starts out with pieces I find self-indulgent, but picks up as the selected works begin to explore the idea of utopia. Some highlights for me were the walk-inside Knowledge Box by Ken Isaac, the prints of Black Panther artist Emory Douglas, and the inclusion of Victor Papanek and Buckminster Fuller.

But the artist who I was most glad to meet for the first time was Öyvind Fahlstrom. He first got my attention just inside the entrance with this large, wall-mounted piece:

ESSO-LSD (1967)

Which I didn't claim understand, but assumed was a bit of arch pop-art commentary.

So imagine my surprise when I had almost reached the end of the exhibit and I came across this completely different piece, also by Fahlström:

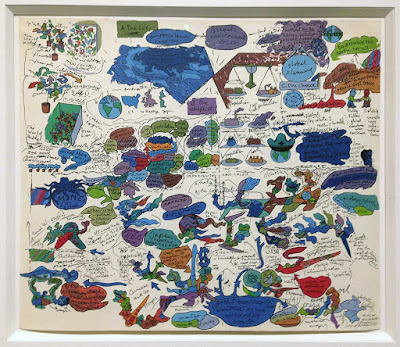

Study for World Model (Garden), 1973

The sketch is only about two feet wide, so it's pretty small for the number of images within it. I responded to both its organic, exploratory form and the color. I'm a sucker for artists with a message, and I have a high tolerance for the didactic.

Studying it more closely, I found Fahlström struggling to synthesize many of the same problems we face today. How "to preserve the earth for all"? Through world revolution? Global planning? "Or at least cooperation between countries a on a non-profit people-first basis." "Socialist or not."

He noted that "profit-based capitalism economies require accelerative growth." Which was a not-uncommon topic at that time that has once again become important.

And what was the future of the developing world, particularly? "GNP —> no measure for development." "'AID' as imperialism." Plus a bunch of other words I can only partly decipher.

Intrigued and promising myself I would look him up when I got home, I imagined that was that for Fahlström in the show until I walked a bit farther on and saw a darkened doorway. A museum guide stood outside, making sure visitors took off their shoes before stepping onto the kelly green carpeting.

The room was full of cutouts painted in bright colors and lettered in India ink, then attached to wooden dowels that stood up in clay flower pots. The green carpet was part of it, as was the lighting, which cast undulating shadows beneath. It was another work by Fahlström, the finished piece he made after the small study:

Garden — A World Model, 1973

The style is more finished than the sketch, clearly a form of didactic comic. Was Fahlström's work influential on the development of that form?

I wondered where this piece was shown at the time. It's currently housed in the collection at MACBA, the contemporary art museum of Barcelona, on long-term loan from Fahlström's widow.

Remember, the piece is from 1973. This part of it says "new nationalist Arab states will nationalize [oil] and control prices." The two guys with the guns are tagged Iran, which was still under the Shah at this point, and Israel and described as "client states" that "guard Western oil interests." I wonder when exactly Fahlström created Garden in 1973? The oil crisis that year didn't begin until October when OPEC started its oil embargo.

The MACBA site says of Garden,

Conceived as a lush garden and presented as an environmental tableau, [Fahlström] creates an aerial structure using flowerpots and wooden rods. Over the flowers he unfolds a visual narrative that uses the aesthetic of comics and offers numerous economic and political facts.At one point the text of Garden explains that poor peasants are driven out of business by the "green revolution" even as agribusiness benefits through its "'miracle' wheat and rice" that "require high technology farming equipment / pesticides / fertilizers (MOSTLY ESSO) POLLUTION." Which shows that this 1973 Fahlström work does relate to the 1967 ESSO/LSD pop art at the beginning of the show.

In a similar vein to the talking paintings of the rhetoric tradition, nature talks in the volatile and floating language of information: a world map of drawings, texts and data crowds in to the images, organised into different sections. The communicative loquacity of the plants evokes a corrupt, contaminated and irrational world. The work has been compared to Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, in which artificial delirium triumphs in a place that is supposedly dedicated to nature.

Inspired by writers such as Antonin Artaud and Willian Burroughs, Fahlström sets up a labyrinthine logic with rules that must be set by each spectator. In keeping with the idea of Medieval maps, the artist offers a dual reading: the visual language of pop culture allows a straightforward approach, while the geopolitical references and the complex connections address a more limited audience.

After reading this writer's detailed thoughts about the Garden installation, I think I will go back to spend more time with it before Hippie Modernism closes in February.

Öyvind Fahlström died of cancer in 1976 at age 47.

No comments:

Post a Comment