I read Geoff Herbach's YA novel Stupid Fast -- er, pretty darn fast. I heard about it from Molly Priesmeyer on Twitter. Not sure if she knows Herbach personally or what (I don't get the impression she's a regular YA reader), but she had praised it pretty roundly, and I thought it sounded like it would be worth a try. So I stopped by Red Balloon Bookshop, assuming they would have it, and I wasn't disappointed!

I read Geoff Herbach's YA novel Stupid Fast -- er, pretty darn fast. I heard about it from Molly Priesmeyer on Twitter. Not sure if she knows Herbach personally or what (I don't get the impression she's a regular YA reader), but she had praised it pretty roundly, and I thought it sounded like it would be worth a try. So I stopped by Red Balloon Bookshop, assuming they would have it, and I wasn't disappointed!

I almost left without buying the book when I saw the cover, though: It shows a teen boy in a football uniform, sitting with his back to the viewer. But I held my nose in an effort to ignore my bias against sports novels and picked it up anyway. While I was checking out, the worker at the counter exclaimed over the book and said her son had just read it and was going to be writing about it for a teen book group.

So, without giving anything away, I'll just say: it has a great character voice, Pete Hautmanesque story-telling, and a deft recognition of human complexity. Bonus: It's set in southwestern Wisconsin.

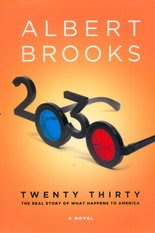

I had to read Stupid Fast to recover from reading Albert Brooks's Twenty Thirty. I like to think I have pretty good taste in books, to the point where I buy them in hardcover and am happy to keep them in perpetuity at least 90 percent of the time. But Twenty Thirty is one of the ten percent that will find its way to Half Price Books soon.

I had to read Stupid Fast to recover from reading Albert Brooks's Twenty Thirty. I like to think I have pretty good taste in books, to the point where I buy them in hardcover and am happy to keep them in perpetuity at least 90 percent of the time. But Twenty Thirty is one of the ten percent that will find its way to Half Price Books soon.

It's near-future science fiction, usually one of my favorites, but Brooks floats a couple of interesting concepts about the coming clash between debt-ridden youth and the Medicare-loving "olds" who seem like they'll live forever, and then flounders through the maze of characters he's created as though he's checking off items on a plot outline. As I read through it, I could never keep track of which character was which, although I usually have no trouble with that sort of thing in books with multiple story lines. Maybe it was all the boring names Brooks gave them, or the fact that they felt like caricatures instead of people.

Nice cover, though -- but not a good example of judging a book by it. I should have trusted my usual mistrust of books written by celebrities. In this case, I thought the celebrity could write, but I guess novels are not his thing.

I may have found Twenty Thirty particularly disappointing because I read it right after reading James Howard Kunstler's doomer bible The Long Emergency: Surviving the End of Oil, Climate Change, and Other Converging Catastrophes of the Twenty-First Century. While Kunstler is harsh, I like to think I was pretty prepared for him, so it didn't depress me too much.

I may have found Twenty Thirty particularly disappointing because I read it right after reading James Howard Kunstler's doomer bible The Long Emergency: Surviving the End of Oil, Climate Change, and Other Converging Catastrophes of the Twenty-First Century. While Kunstler is harsh, I like to think I was pretty prepared for him, so it didn't depress me too much.

Kunstler's premise, as is pretty widely known, is that we've just passed peak oil, worldwide. He spends his time spinning scenarios of what will happen to daily life and the economy once we no longer have access to cheap, portable fuel. He (somewhat gleefully, it seems to me) shoots down the "cornucopian" arguments of those who think technology will save us (hydrogen fuel cells, as well solar, wind and nuclear power). The upshot: small cities and large towns are the places to be, especially in parts of the country that have access to fresh water and the possibility of hydro power. Hence, his home in upstate New York north of Albany. Do everything you can to be prepared for your new career as a subsistence farmer, or maybe a carpenter or shoemaker.

Some revelations I found in the book:

- The success of Thatcherism had a lot more to do with the North Sea oil boom (now over) than it did with the correctness of conservative policies.

- The U.S. energy crises of 1973 and 1979, which I experienced as a teenager, were all about the passing of the U.S. oil peak, and the transition to control of supply by other nations (OPEC). The fact that prices and supplies then eased for such a long time is also explained (see the bit about North Sea oil, above). All of which Americans took as an excuse to forget about energy conservation, building farther out from city centers, flying more and more, moving up to SUVs, and killing what was left of our railroads.

- The U.S. will never give up its swollen military budget as long as there's a drop of oil to be controlled worldwide. I don't mean to say I didn't realize we've been fighting wars for oil. I just hadn't quite internalized how deep-seated our nation's attachment to its military budget is.

- Despite the fact that Kunstler wrote the book in 2004, with publication early in 2005, he completely nailed the Wall Street stock casino, the housing bubble and the subsequent implosion. It was eerie reading his description.

Our ability to resist the environmental corrective of disease will probably prove to have been another temporary boon of the cheap-oil age, like air conditioning and lobsters flown daily from Maine to the buffets of Las Vegas. So much of what we construe to be among our entitlements to perpetual progress may prove to have been a strange, marvelous, and anomalous moment in the planet's history (page 12).With Michele Bachmann promising $2 a gallon gas if she's elected, and now saying she would drill in the Everglades (while also eliminating the EPA so no environmental checks could be done), Kunstler is more timely than ever. Reading The Long Emergency, I have to say I became convinced that -- barring a cornucopian invention of free flowing energy -- we're about to experience a crashing oil hangover. The best we can hope is that it happens gradually and not suddenly. But given our political climate, I don't think gradual is in the cards.

When media commentators cast about struggling to explain what has happened in our country economically, they uniformly overlook the colossal misinvestment that suburbia represents -- a prodigious, unparalleled misallocation of resources (page 17).

I do not believe that the general ignorance about the coming catastrophic end of the cheap-oil era is the product of a conspiracy, either on the part of business or government or news media. Mostly it's a matter of cultural inertia, aggravated by collective delusion, nursed in the growth medium of comfort and complacency (page 26).

Fossil fuels provided for each person in an industrialized country the equivalent of having hundreds of slaves constantly at his or her disposal (page 31).

Globalism was primarily a way of privatizing the profits of business activities while socializing the costs (page 186).

The dirty secret of the American economy in the 1990s was that it was no longer about anything except the creation of suburban sprawl and the furnishing, accessorizing, and financing of it. It resembled the efficiency of cancer (page 222).

No comments:

Post a Comment